Food Insecurity in the Local Community: Going from Invisible to Equitable

In light of the current economic crisis and inflation rates in the United States, families are struggling to put food on the table. According to Feeding America, a non-profit dedicated to ending hunger, over 25% of families remain food insecure, meaning that more than 16 million American children are affected nationally.

Food insecurity is best defined as inconsistent access to sufficient or nutritious food. It is a multi-faceted problem, taking different forms in each affected household.

Some struggle to provide food for themselves and their families due to unemployment, while others remain employed but cannot afford to provide three nutritious meals daily due to the current economic market. However extreme or temporary, people under economic strain deserve the resources to access nutritious foods.

Within New Hampshire specifically, 1 in 11 children face hunger, affecting a child’s growth, mental capacity, stress levels, and attention span within a school day. Ultimately, food insecurity creates an equity barrier.

Although many national programs, such as SNAP and free or reduced meal plans, attempt to combat hunger, they do not provide enough relief on their own. Many households would benefit from increased temporary aid systems to assist with food access, regardless of their employment status or in which community they reside.

In the Seacoast community, the question often remains unanswered: What does food insecurity look like here?

According to Kate Constantine, the pantry coordinator at Gather, the issue is largely invisible to some and often misunderstood by many in the Seacoast: “Many people don’t know what food insecurity looks like, so they resort to the extremes. Because of that, a lot of people don’t think it’s an issue here.” She says, “Anyone can be food insecure at any time. We must break the food insecurity stigma to better combat the issue.”

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, Gather saw an exponential increase in need on the Seacoast. The pantry went from serving roughly 3,000 families per month pre-pandemic to 9,000 per month in 2023.

Constantine continued, “It’s a good thing we are seeing such an increase in members. It means that people are no longer afraid to ask for help.” Constantine worries that the looming stigma surrounding food insecurity results from the false narratives that prevail within society: “We need to rework the narratives of what it means to be food insecure. It should not be an embarrassing thing.”

Reworking the narratives surrounding food insecurity is a complicated process. The community must raise awareness, and redefine what it means to be food insecure.

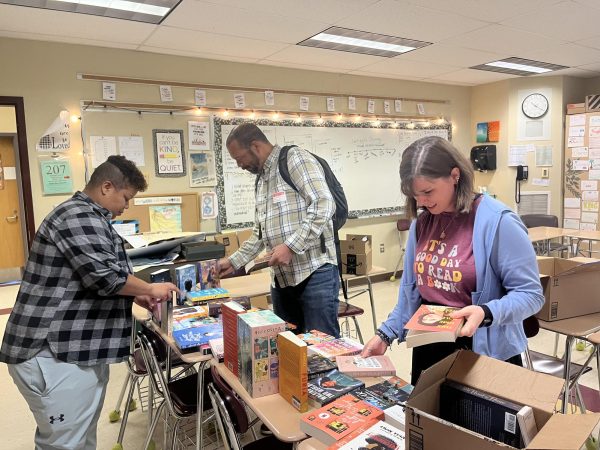

At Dover High School, social worker Donna Frank-Berchulski started a food pantry initiative to assist high school students: “ In high school, it becomes harder to help the students who need it.” She said, recalling the origins of the in-school food pantry, “I started gathering food for students… some snacks during the day, meals, and food to take home. Any student can visit me at any time, and I’ll fill a backpack of food for them, or offer them some snacks… however I can help.”

The pantry setup helps to prevent student self-consciousness while providing aid. After a few weeks, word spread within the school, and the pantry saw rapid increases in food, gift card, and financial donations to the food pantry.

The Dover National Honors Society, student council, and other organizations made the food pantry the destination of their fundraising endeavors.

Additionally, outside organizations such as the locally owned Red’s Shoebarn store, and Dover Pediatrics donate items and monetary donations to the cause.

Hesitations may arise about potential abuse of the initiative, such as students taking food when they don’t need it. However, the snack portion of the pantry is meant to be open to any student, at any time, whereas the take-home aspect of the pantry is arranged and managed by Frank-Berchulski and her colleagues in the guidance office.

Overall, little concern remains for Frank-Berchulski about the abuse of the initiative, and she has yet to have issues with this aspect.

In fact, Frank-Berchulski is elated by the impact: “People are so excited to help out. Not only does it show the strength of our community, but it also shows how much the issue of teenage wellness is being addressed.”

In the future, Frank-Berchulski hopes the pantry continues to thrive and provide students with equitable access to food whenever they need it.

Community-driven efforts such as an in-school pantry may be the key to reworking the narratives surrounding food insecurity while breaking the stigma surrounding the issue.

Sources:

Constantine, Kate. In-person interview. February, 2023.

Feeding America. “Feeding America: New Hampshire.” Feeding America, www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/new-hampshire. Accessed 16 Feb. 2023.

Frank-Berchulski, Donna. Phone interview. February, 2023.

Diana • Mar 27, 2023 at 10:21 am

So informative. I wasn’t aware of the Dover High School food pantry. What a wonderful initiative!! It’s articles like yours that shed some light on what is often an issue that lurks in the shadows. Thanks Gabby!