In the United States, the Bill of Rights protects all persons within its borders, however, there are a few exceptions. Students at school are one of them. It begs the question, how are students protected against searches and seizures as listed in the Fourth Amendment?

The Fourth Amendment protects Americans, their houses, papers, and effects from unreasonable searches and seizures with the exception of a warranty upon probable cause.

New Jersey v. T.L.O, a 1985 U.S Supreme Court case highlights student search rights at school.

T.L.O. was a 14 year old female student at New Jersey high school who was found smoking cigarettes with a friend. Her friend admitted to smoking to an administrator but T.L.O denied the allegations.

The administrator demanded to see inside of her purse to find the cigarettes and found drug paraphernalia including a pipe, money, and a piece of paper with the names of students who likely owed T.L.O money.

Her mother was later notified by the police. At the station, T.L.O confessed to selling marijuana and faced charges in juvenile court.

T.L.O’s lawyer argued to the New Jersey Supreme Court that the school’s search was against her Fourth Amendment right.

The New Jersey Supreme Court held that the search did not violate her rights as the school was allowed to search a student if an official has reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed or is in the process of being committed.

In Portsmouth

At Portsmouth High School, the student handbook’s rule on student searches comes directly from Portsmouth School Board Policy JIH.

It states that searches may occur if “any authorized person has reasonable suspicion that the student may have on their person or property: alcohol, weapons, prohibited electronic devices, controlled substances [and] stolen property,” and clarifies that, “lockers, desks, and other storage areas or compartments have no reasonable expectation of privacy.”

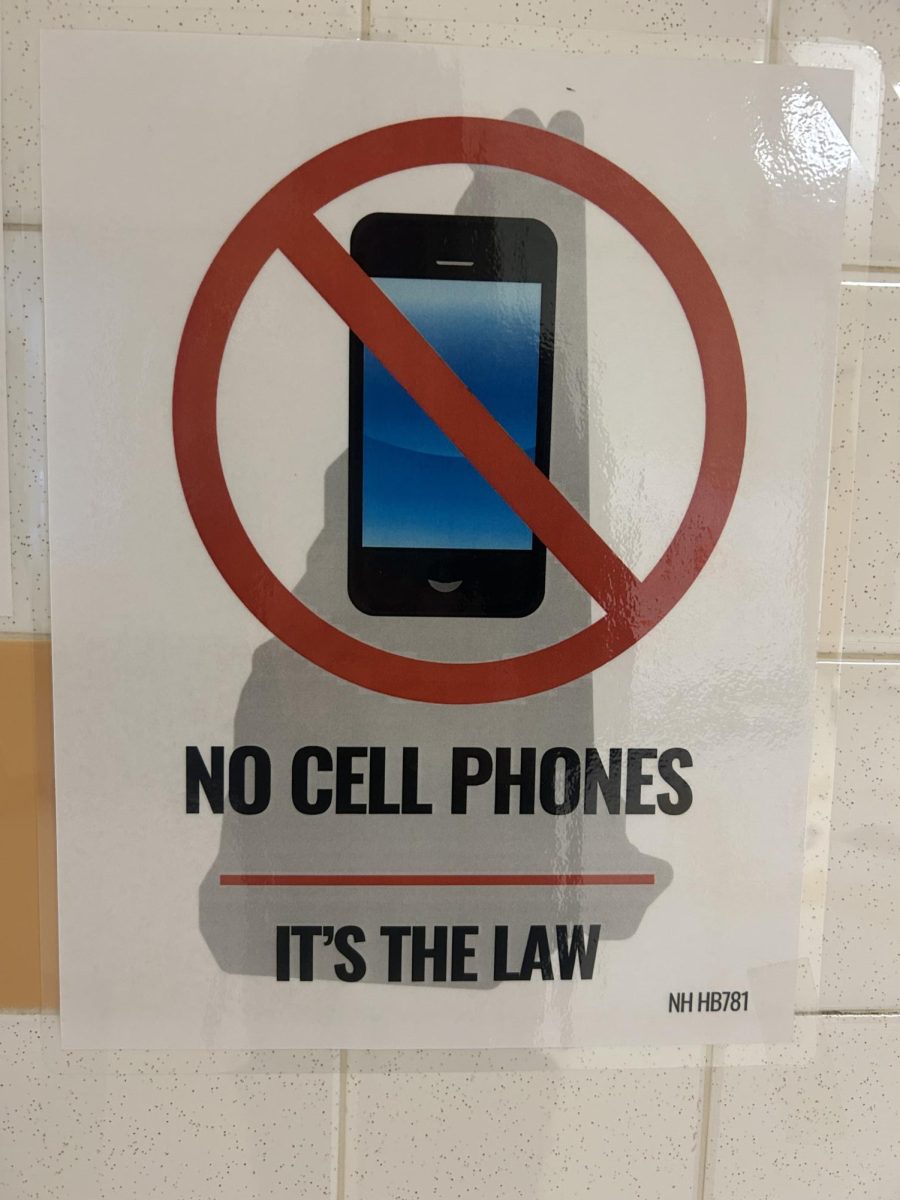

As of the 2025-2026 school year, New Hampshire Governor Kelly Ayotte passed a statewide bell-to-bell phone ban in K-12 education.

The statewide law states, “policy [created by school districts] shall prohibit all personal communication device use by students from when the first bell rings to start instructional time until the dismissal bell rings to end the academic school day.”

At PHS, the rule requires students to either keep their phones in their first block class right when the bell rings, keep them in their car, or at home.

What Others Know

In a poll by the M-A Chronicle, a student online publication, it found that almost a quarter of selected students thought their rights were the same in and out of school.

Sophomore Hannah Gordon was aware that PHS can search you for drugs, drug paraphernalia, vapes pens, weapons, and alcohol. However, she admits that she could benefit from learning more about her rights as a student.

“I know they’re allowed to look through your bag if they have reason,” Gordon expanded.

She acknowledged that, “there’s a good chunk of the school who potentially keep something in their bag [that] they shouldn’t,” which she found concerning.

Norah Blakey, a junior at PHS, had vaguely heard of the school’s search and seizure rights.

“Based off of what teachers have said to me and other students, I’ve found that they seem very comfortable threatening to search us if they see something resembling a phone on our person,” she noted.

An Administrative View

Shawn Donovan, an assistant principal at PHS, commented on Policy JIH and related issues from the student body.

Donovan is involved with this policy on a frequent basis and was able to clarify potential concerns from students and parents.

In a non-legal scenario, he states that, “when students are with us we’re in loco parentis.”

The term “loco parentis” is Latin for, “in place of a parent or instead of a parent.

Cornell Law School refers to it as “common law doctrine which denotes the legal responsibility of some person or organization to perform some of the functions or responsibilities of a parent.”

It gives the school the ability to search you in the place of a parent if there is a reasonable suspicion or probable cause.

Portsmouth School Board Chair Nancy Clayburgh stated, “as far as the cell phones are concerned, it’s something that is— it’s a state law now. So the state law supersedes, you know, any local policy or law that exists. So as far as the cell phones go, there was no choice for the local school district.”

Staff Involvement

Zachariah Goldenberg, a math teacher at PHS explained that, “My understanding is that if the administration has enough credible evidence, whether it be a reliable tip or other source of information, that they have grounds to search your property based on reasonable suspicion. I’m not aware of any teachers conducting these searches, instead they would pass information along to the administration to handle.”

He noted that there is still some student misunderstanding of their property in this policy. Goldenberg brought up the situation of voluntary or involuntary searches.

“In regards to voluntary searches, a student may be asked by the administration if they can search their bag without the burden of reasonable suspicion and the student may accept or decline,” he stated.

Laura LaVallee, an English teacher and club advisor at PHS, had a different perspective on the search and seizure policy. As a mother, LaVallee additionally brought her concerns but also appreciation of the phone ban into discussion.

LaVallee was unaware that students could potentially be searched for their cell phones and extended with, “I am personally not comfortable searching anyone, but I am glad that we have the resources in order to conduct a search if necessary.”

“I’m assuming that most of the students keep their phones in their backpacks, and although it’s preferred they leave them in their first block class,” LaVallee observed. “The students, from my experience, have done a great job of keeping their phones out of sight during the school day.”

What The Community Can Do

Donovan advised students to “read the student handbook, know what’s in there,” to keep them informed and knowledgeable about their rights.

Clayburgh attested the standards of the School Board and said, “if students or civilians want to question any policy that we have, they can, they have every right to come to a meeting and talk to us during the public comments section of the meeting.”

For any concerns about your school’s search and seizure policy, reach out to your local school board and school administration.